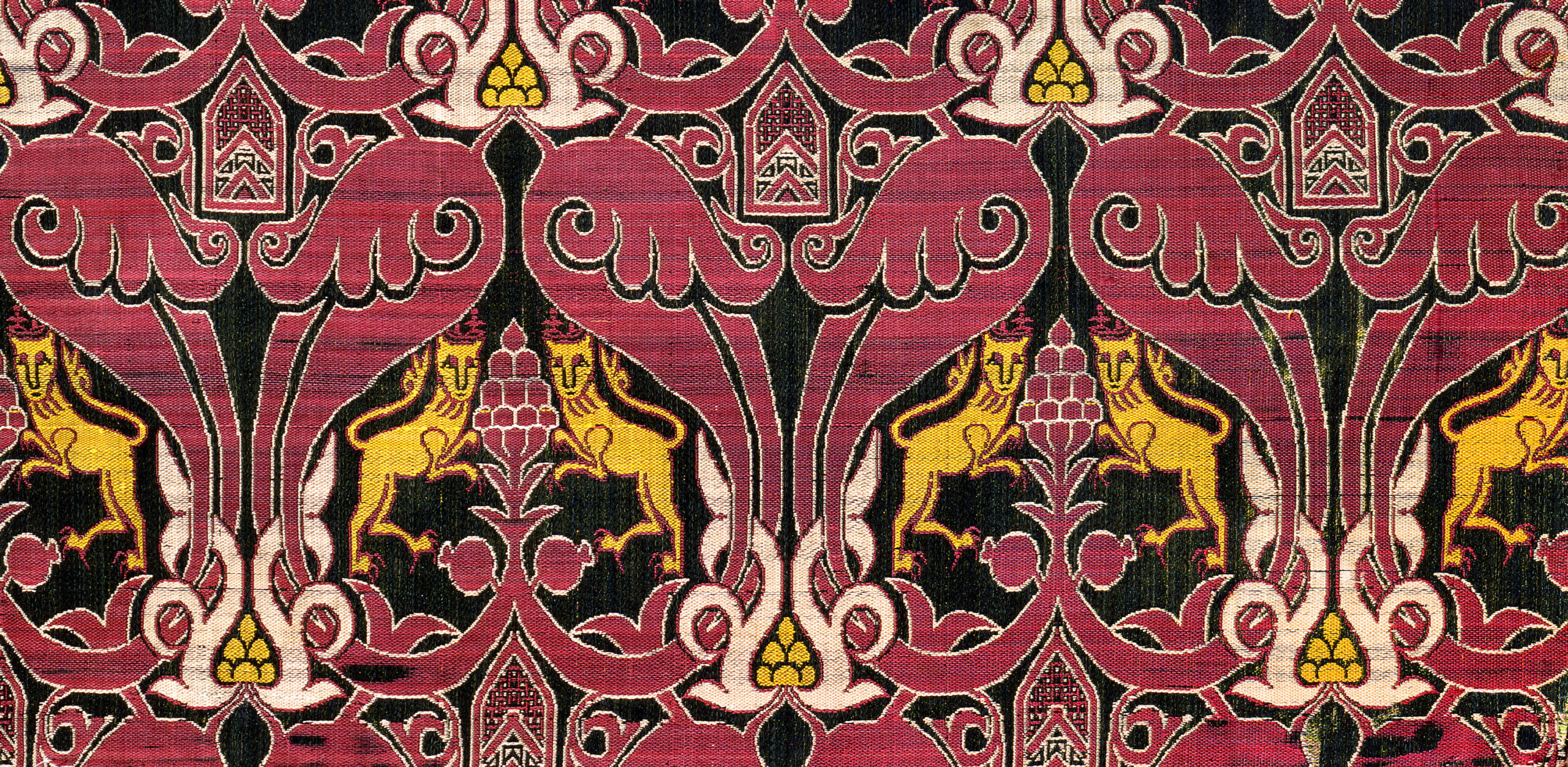

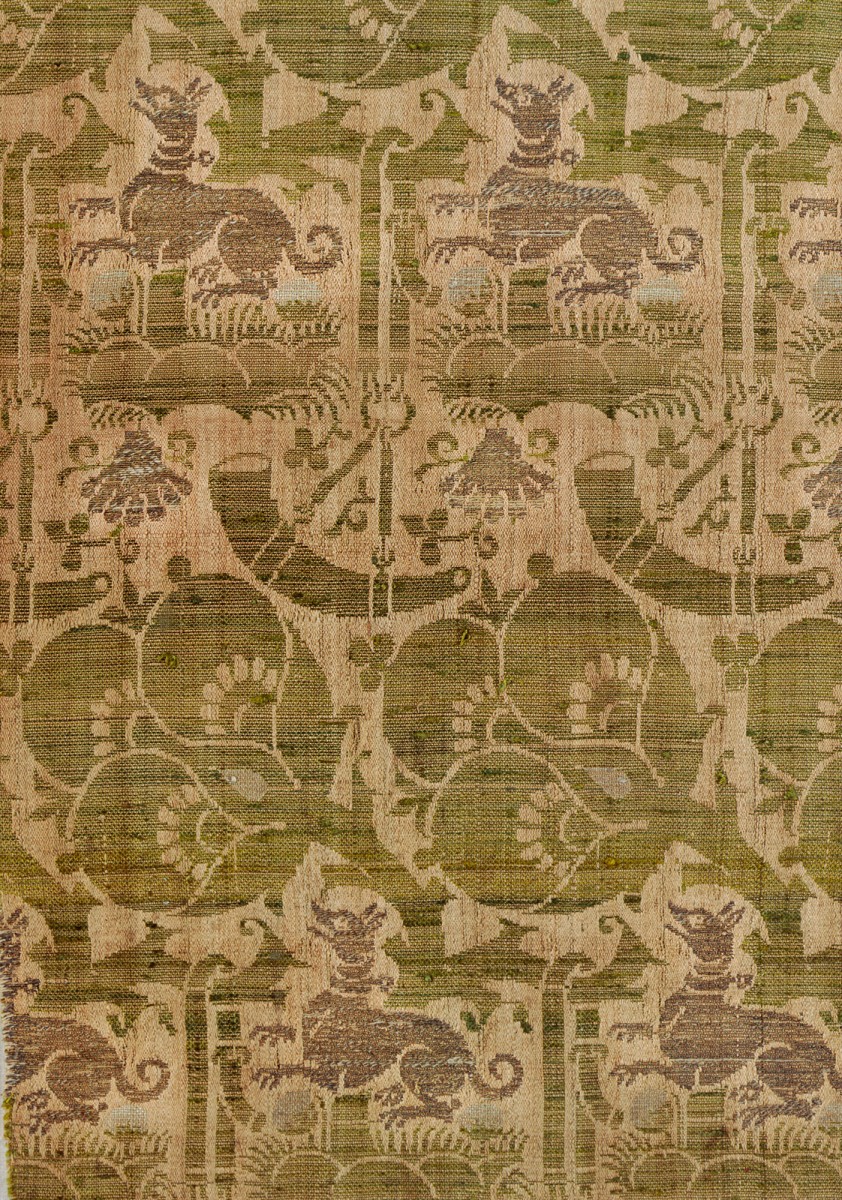

22 September – 13 November 2016 Friend and Foe – Animals in Medieval Textile Art

Eagles, gazelles, lions and peacocks in all their glory – animals bring to life the textiles in which society’s elites once clothed themselves. These luxury fabrics are material testimony to an aristocratic culture. Their representations play on hunting as a privilege of the nobility or on the concept of courtly love. Drawing on literary texts from Ovid’s Metamorphoses to medieval romances and Minnesang love poetry, the special exhibition 2016 sheds light on the meaning of these fairy-tale-like textile images.